This happened in refrigerant development during the past year

written by Pavel Makhnatch (under supervision of Rahmatollah Khodabandeh and Björn Palm)

This year was yet another exciting year in refrigerant development. New international agreements have set a clear aim to reduce the amounts of used fluorinated greenhouse gases. “F-gas regulation” is no longer a new regulation, but instead the regulation that is accounted for by many. New refrigerants are being studied as alternatives to the conventional refrigerants with high GWP, and the attention to “natural refrigerants” is growing. Even new alternative technologies are considered as a solution to the existing environmental problems. In this article we discuss the major events that will likely affect the refrigerant choice in the future.

Global climate agreements

Just a year ago we have discussed the possibility of global agreement on HFCs reduction within the Montreal Protocol mechanism. Then, a number of countries have submitted their proposals on what the HFC phase down schedule can look like. Although the proposals were different in their reduction schedule and baseline years selection, there was a clear agreement to address the global consumption and production of HFC. After about a year since then, the global agreement is now a fact.

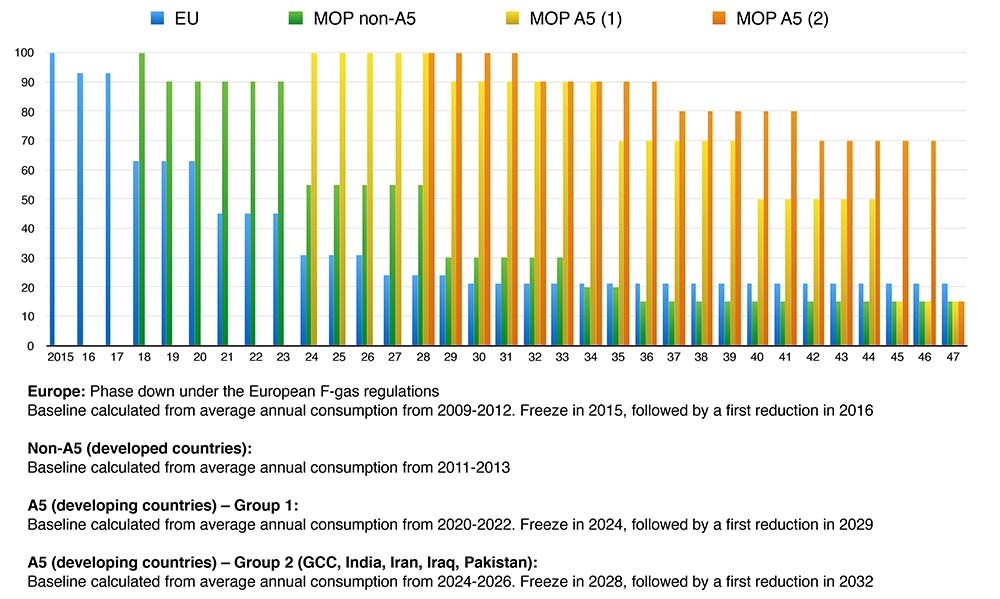

The 197 Montreal Protocol parties reached a compromise, under which developed countries will start to phase down HFCs by 2019. Developing countries will follow with a freeze of HFCs consumption levels in 2024, with some countries freezing consumption in 2028. By the late 2040s, all countries are expected to consume no more than 15-20 per cent of their respective baselines, Figure 1 (UNEP, 2016). This is believed to avoiding up to 0.5° Celsius warming by the end of the century.

Noticeably, a number of developing countries will start their reduction later than other developing countries, since they represent countries with high ambient temperatures. These countries have increased demand for the cooling and need efficient replacements to R22 that is still being used there.

F-gas regulation

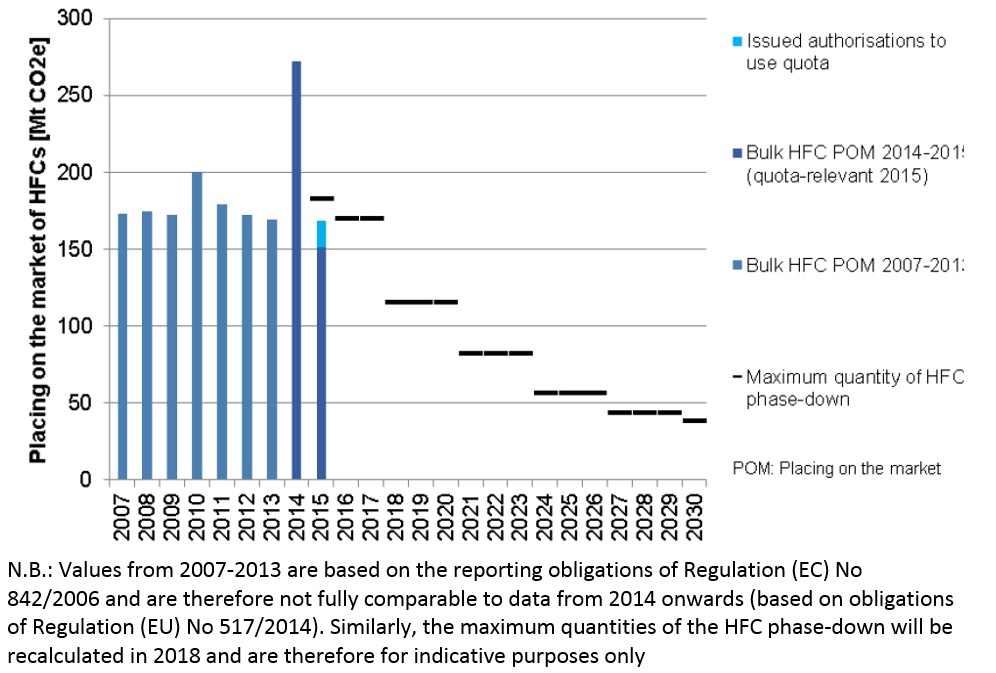

While Montreal Protocol agreement on HFC reduction is without any doubt important, in the EU the use of fluorinated gases is regulated by the Regulation 517/2014, so called “F-Gas Regulation”. Its HFC phase down schedule is more ambitious and in about a year from now the amount of fluorinated gases that are newly introduced in the EU market will need to be significantly reduced: to 63% of the baseline 2009-2012. Notable, no bans that can facilitate such reduction are required by the F-gas regulation until that time.

The HFCs statistics so far shows that there was reduction of 8% in 2015 (1% greater than required by the F-gas regulation), although that was preceded by the consumption peak in 2014, the year where no limitation were put (European Comission, 2016)

As a respond to the required reductions, in the end of the last year all major chemical companies have announced a 10-15% price increase for a number of the refrigerants, including R134a, R404A and R410A (Makhnatch et al., 2015). Recently, Mexichem has announced a further price increase of 20% for R404A and R507, 15% for R134a, R410A, R407C, and 10% for R407A (Mexichem, 2016). Other companies are likely to introduce similar increases this year as well.

MAC Directive

While F-gas regulation do not require any HFC reduction next year, the so called “MAC Directive” (European Parliament, 2006) stated that the use of fluorinated greenhouse gases with a GWP higher than 150 in all new vehicles put on the EU market will be totally banned from the beginning of the next year. New vehicles with MAC systems using these gases will not be registered, sold, or able to enter into service in the EU (EU, 2006).

As for the moment, R1234yf (developed in collaboration between the two major chemical manufacturers) is the refrigerant of a choice for MACs. Previously, Daimler has expressed concerns about safety of R1234yf in MACs and announced that it will develop the CO2 MAC system together with several other automakers (R744, 2013)(R744, 2015). There is no further updates on whether such system is being developed or not.

New refrigerants

Clearly, many conventional refrigerants will be replaced with other more environmentally friendly refrigerants in the future. Selection of a refrigerant is always a trade-off of a number of properties. Now, when the environmental properties gained higher weight in the refrigerant selection process, proposed refrigerants have properties that are previously were not widely acceptable, as for example high temperature glide, increased discharge temperatures, flammability and etc.

The amount of single component refrigerants with GWP below 200 is limited, and we are unlikely to see many new single component refrigerants with GWP below 200 in the future (Kazakov et al., 2012). The demand will therefore be covered by the limited amount of the single component refrigerants and a number of their mixtures. As for the latter, the number of the mixtures listed in the ASHRAE Standard 34 and its amendments is greater than a hundred and new mixtures are being added constantly. For further discussions about the new refrigerants and mixtures please refer to another publication “ Environmentally friendly refrigerants of the future ”.

New technologies

In addition to conventional vapor compression cycle that is utilized in most of the ref system today there is a growing interest to alternative refrigeration cycles. Absorption/adsorption, thermoelectric and air compression cycles has been known for years and are used in niche applications. A rather promising technology is the magneto-caloric cycle that has gained a lot of attention in the recent years. It becomes attractive due to recent developments in the materials and prototypes being manufactured.

Other technologies that are being developed include thermoacoustic refrigeration, thermotunneling, Stirling cycle refrigeration, pulse tube refrigeration, Malone cycle refrigeration and compressor driven metal hydride heat pumps. Although some of these technologies can be quite efficient, the developments in this area are still at the early stages.

Refrigeration and climate change

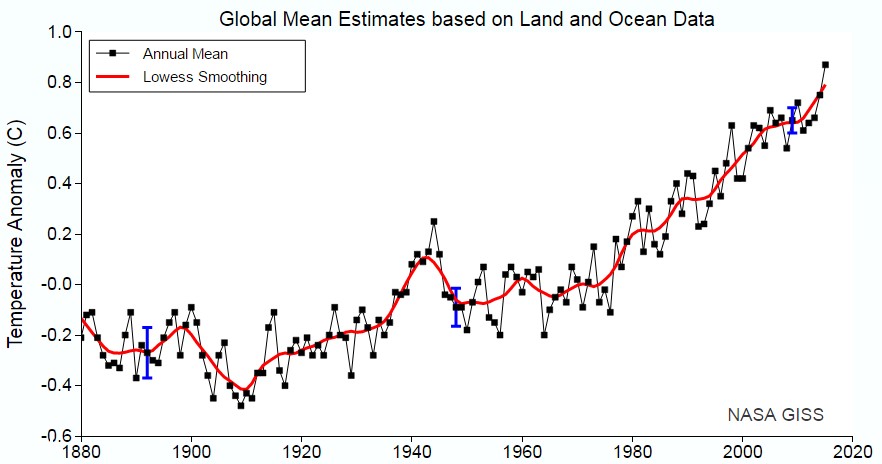

All in all, there is a clear need to combat climate change. This is included in the aim of the recent Paris Agreement that has been adopted last December and entered into force on 4th November this year. Within the agreement, countries agreed to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change (UNFCCC, 2016).

At this time, the climate observations show that years 2011-2015 have been the hottest years on record globally, and the current year is no exception, Figure 3 (GISTEMP-Team, 2016). The warmest year on record to date was 2015, during which temperatures were 0.76 °C above the 1961–1990 average, followed by 2014. The year 2015 was also the first year in which global temperatures were more than 1 °C above the pre-industrial era (World Meteorological Organization, 2016).

Refrigeration industry can contribute to the climate change mitigation by replacing refrigerants with more environmentally friendly alternative, as well as implementing more energy efficient systems and solutions. In addition to the climate benefits, this process is seen as a business opportunity for many that are involved in the refrigeration industry. From our side we will continue to timely review the developments in the area of environmentally friendly refrigerants.

References

Cooling post, 2016. The global HFC phase down – how it looks [WWW Document]. URL http://www.coolingpost.com/features/the-global-hfc-phase-down-how-it-looks/

EU, 2006. Directive 2006/40/EC of the European Parliament and of the council of 17 May 2006 relating to emissions from air-conditioning systems in motor vehicles and amending Council Directive 70/156/EEC. Off. J. Eur. Union.

European Comission, 2016. Progress of the HFC Phase Down.

European Parliament, 2006. Directive 2006/40/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2006 relating to emissions from air conditioning systems in motor vehicles and amending Council Directive 70/156/EEC. Off. J. Eur. Union.

GISTEMP-Team, 2016. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP) [WWW Document]. NASA Goddard Inst. Sp. Stud. URL http://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/

Kazakov, A., McLinden, M.O., Frenkel, M., 2012. Computational Design of New Refrigerant Fluids Based on Environmental, Safety, and Thermodynamic Characteristics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 120917100332001. doi:10.1021/ie3016126

Makhnatch, P., Khodabandeh, R., Palm, B., 2015. Utvecklingen på köldmediefronten under året som gått. KYLA+ Värmepumpar.

Mexichem, 2016. Mexichem’s Fluor Business Group to Increase Price of Klea® Refrigerants in Europe [WWW Document]. URL http://www.mexichemfluor.com/news/2016/10/mexichems-fluor-business-group-to-increase-price-of-klea-refrigerants-in-europe/

R744, 2015. Mercedes commits to CO2 MAC from 2017 [WWW Document]. URL http://www.r744.com/articles/6709/mercedes_commits_to_co_sub_2_sub_mac_from_2017

R744, 2013. Daimler, Audi, BMW, Porsche and VW to develop CO2 MAC systems - Third time lucky? [WWW Document]. URL http://www.r744.com/articles/3957/daimler_audi_bmw_porsche_and_vw_to_develop_co_sub_2_sub_mac_systems-third_time_lucky

UNEP, 2016. Press Releases October 2016 - Countries agree to curb powerful greenhouse gases in largest climate breakthrough since Paris - United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) [WWW Document]. URL http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=27086&ArticleID=36283&l=en (accessed 11.7.16).

UNFCCC, 2016. The Paris Agreement - main page [WWW Document]. URL http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php (accessed 11.2.16).

World Meteorological Organization, 2016. The global climate 2011-2015: hot and wild [WWW Document]. URL http://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/global-climate-2011-2015-hot-and-wild