Understanding refrigerant flammability

written by Pavel Makhnatch (under supervision of Rahmatollah Khodabandeh and Björn Palm)

In the world of constantly evolving refrigerant options the question of refrigerant flammability is often raised when discussing low GWP refrigerant alternatives for the future. In this publication we would attempt to describe and structure the question of refrigerant flammability.

Main flammability characteristics

Flammability is a property of a mixture in which a flame is capable of self-propagating for a certain distance [1]. Generally speaking, flammability of a refrigerant is its ability to burn or ignite, causing fire or combustion. The degree of difficulty required to cause the combustion of a substance is quantified through fire testing and dependent on a number parameters discussed below.

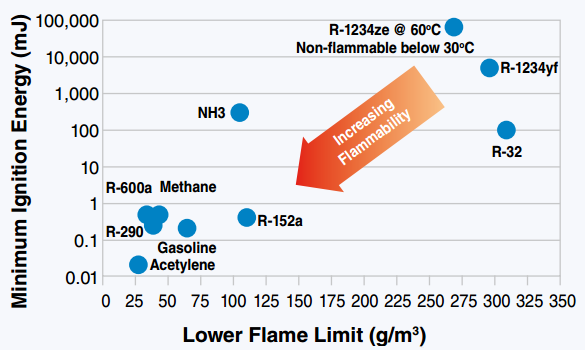

When the substance is flammable depends on the upper and lower flammability limits and the supplied energy for ignition. The consequences of the flammability event depend on the burning velocity, heat released and byproducts of combustion.

Mixtures of refrigerant and air will burn only if the fuel concentration lies within well-defined lower and upper bounds determined experimentally referred to as flammability limits.

Lower flammability limit (LFL, % by volume or g/m3): minimum concentration of the refrigerant that is capable of propagating a flame through a homogeneous mixture of the refrigerant and air under the specified test conditions at 23.0 °C and 101.3 kPa [1]. At a concentration in air lower than the LFL, gas mixtures are too weak to burn. Methane gas has a LFL of 4.4%. If the atmosphere has less than 4.4% methane, combustion cannot occur even if a source of ignition is present.

Upper flammability limit (UFL) is the highest concentration of a gas or a vapor in air capable of producing a flash of fire in presence of an ignition source (arc, flame, heat). Concentrations higher than UFL are "too rich" to burn.

Figure 1 presents minimum ignition energy and lower flammability limits for a number of different refrigerants.

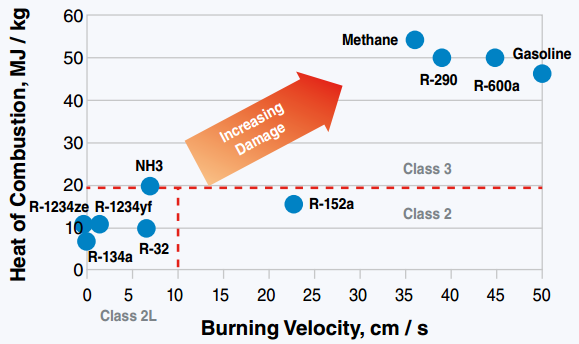

Burning velocity is velocity relative to the unburnt gas (normally in sm/s), at which a laminar flame propagates in a direction normal to the flame front, at the concentration of refrigerant with air giving the maximum velocity [1].

Heat of combustion is the heat evolved from a specified reaction of a substance with oxygen.

Figure 2 presents minimum ignition energy and lower flammability limits for a number of different refrigerants.

Standards and classification

Standards provide limitations and recommended practices on how to properly handle different refrigerants, including flammable ones.

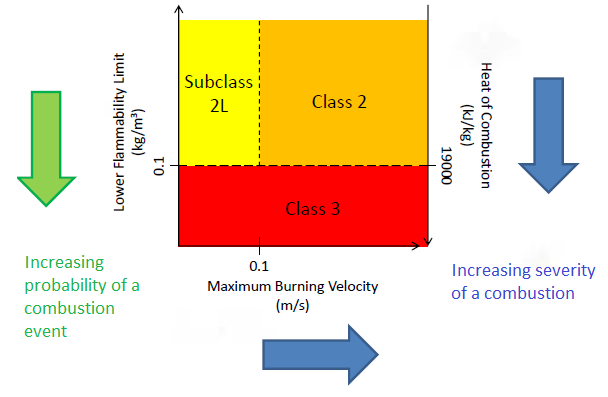

ASHRAE standard 34 “Designation and Safety Classification of Refrigerants” classifies refrigerants based on their flammability and toxicity characteristics. It recognizes several flammability classes from nonflammable A1 to highly flammable A3, depending on refrigerant’s LFL value, heat of combustion and maximum burning velocity (Figure 3).

Similarly to ASHRAE standard 34, standard ISO 817 “Refrigerants -- Designation and safety classification” provides an unambiguous system for assigning designations to refrigerants and its flammability on international levels.

European Standard EN 378 “Safety and Environmental Requirements for Refrigeration Systems and Heat Pumps” aims to reduce the number of hazards to persons, property and the environment, caused by refrigerating systems and refrigerants. It therefore regulates the usage of flammable refrigerants in systems depending on system location, occupancy level, system type and refrigerant used. Current edition of EN378 standard was published in 2008 and do not directly recognizes the A2L flammability refrigerants. It can be expected that the standard will be accordingly updated in its new edition that is currently under development.

In other countries the safety on refrigeration system level is regulated by ASHRAE Standard 15 “Safety Code for Mechanical Refrigeration” (US) and ISO 5149 “Refrigerating systems and heat pumps -- Safety and environmental requirements” (internationally). On the equipment level safety is regulated by, for instance, European standards EN 60335-2-34 and EN 60335-2-40.

Lower flammability refrigerants

To be deemed mildly flammable, a substance must burn at a velocity no greater than 10 sm/s. By comparison, Usain Bolt’s world record 100-metre time equates to 1043 sm/s, while hydrocarbons burn many times faster.

The need for more precise flammability index was proposed in ISO 817 revision working group (WG) in 1999. This proposal was to extend the relaxed anti-explosion requirements for ammonia, which was already well known as difficult to ignite substance, to all similar or lower flammability refrigerants. The WG concluded to employ burning velocity as an additional category in 2002 with the upper boundary of 10 cm/s. This category was named 2L to distinguish from conventional flammable class 2. ASHRAE34 adopted this concept in 2010, while ISO 817 finally adopted in 2014 [2].

In order to ensure safe use of refrigerants with this flammability class and to open up a path for lower GWP refrigerants in the class, experts on the issue have conducted research and development for more than 10 years. Many risk assessments were conducted or being conducted. They indicated that 2L refrigerants’ flammability is acceptable for air conditioners and heat pumps when these systems comply with standards for equipment safety such as EN 378 [2].

Table 1 shows behavior of flame during combustion of different refrigerants. It can be seen, that flame of mildly flammable refrigerants R-32 and ammonia do not propagate horizontally due to their low burning velocities. Additionally the range of impact of the combustion of 2L refrigerants is limited due to their low heat of combustion (that is specifically visible for refrigerant R-32).

Table 1 - Behavior of Flames of different refrigerants [2]

| Classification |

A3 |

A2 |

A2L |

B2L |

| Substance |

Propane |

HFC-152a |

HFC-32 |

Ammonia |

| Burning velocity |

39 cm/sec |

23 cm/sec |

6.7 cm/sec |

7.2 cm/sec |

| Heat of combustion |

46 MJ/kg |

16 MJ/kg |

9 MJ/kg |

19 MJ/kg |

| Combustion state |

|

|

|

|

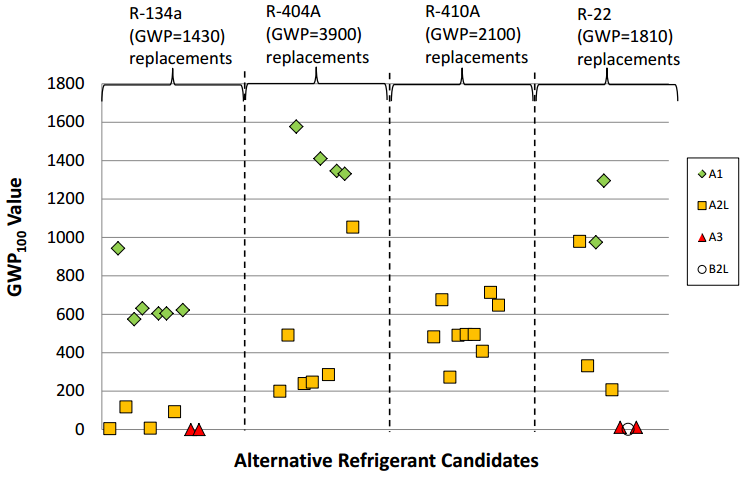

Tradeoff between GWP and flammability

For most refrigerants GWP and flammability are inversely related. Lowering the GWP intrinsically means that the substance is less stable. As such the reactivity, for example flammability increases. This is unavoidable due to the physical characteristics of chemicals [2]. This is valid for most refrigerants. The list of a number of alternative low GWP refrigerants, studied by Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute (AHRI) in their Low Global Warming Potential Alternative Refrigerants Evaluation Program indicate that most of the low GWP alternative are flammable refrigerants [3].

Flammable refrigerants can be safe

As many low GWP refrigerants are flammable it is likely that we will see more equipment that relies on the use of flammable refrigerants. Due to safety concerns mildly flammable A2L refrigerants are most likely to be implemented in replacement to A1 refrigerants.

Additional research efforts are ongoing in the field of refrigerants as for example to improve the accuracy of the ASTM E681 test – test that defines flammable conditions that lead to classifications of a refrigerant [4], develop a set of application requirements for the use of 2L refrigerants [5] and investigate the effect of temperature moisture on flammability [6]

Meanwhile, some flammable refrigerants are already used, as ammonia in industrial applications and hydrocarbons in household refrigerators, as well as recently gaining popularity R32 in domestic air conditioning and heat pump applications [7].

Still, even considering that mildly flammable refrigerants are difficult to ignite and propagate the combustion, it is important to understand that, when combusted, the released products of combustion can be very dangerous.

Följ gärna våra publikationer och få vårt digitala nyhetsbrev. Anmäl dig genom att följa länken bit.ly/kth_ett.

Bibliography

[1] ISO, "ISO 817:2014 "Refrigerants — Designation and safety classification"," 2014.

[2] Daikin, "Flammability and Safety," 2015. [Online]. Available: bit.ly/daikin_flammability.

[3] K. Amrane, "Overview of AHRI Research on Low GWP refrigerants," 2013.

[4] University of Maryland, "ASHRAE grant supports study of refrigerant flammability," 2015. [Online]. Available: bit.ly/ref_safety.

[5] HVACRBusiness, "AHRI Creates Flammable Refrigerants Subcommittee," 2015. [Online]. Available: bit.ly/AHRI_FRS.

[6] S. Kondo, K. Takizawa and K. Tokuhashi, "Effects of temperature and humidity on the flammability limits of several," Journal of Fluorine Chemistry, vol. 144, pp. 130-136, 2012.

[7] Cooling post, "Young Air claims first UK R32 installation," 2015. [Online]. Available: bit.ly/cp_r32.

[8] Honeywell, "Solstice ze refrigerant (HFO-1234ze). The Environmental Alternative to traditional refrigerants.," 2014. [Online]. Available: bit.ly/1234ze

[9] P. Johnson, ” ASHRAE standard 15: proposed changes to incorporate 2L refrigerants,” 2012. [Online]. Available: http://bit.ly/ashrae_2l.